1.3 — Preferences — Appendix

Strict vs. Weak Preferences

We have defined preferences as being strictly one of the following possibilities:

You can also have weak preferences, such as

These are more technically complete, but it is much more simple for us to focus on strong preferences, and we don’t lose much by doing so.

Assumptions of “Well-behaved Preferences”

Reflexivity : any bundle is at least as preferred as itself

Completeness : any two bundles can be compared

Transitivity : rankings are logically consistent:

- If

Are these good assumptions? As you will find typical in economics, very often yes, sometimes no! See the growing field of Behavioral economics for interesting anomalies and exceptions to our assumptions.

Assumptions of “Well-behaved Indifference Curves”

Like preferences, we make 4 major assumptions about indifference curves to describe the normal case. In fact, many of these assumptions are derived from the assumptions we made above about well-behaved preferences

- We can always draw indifference curves: two bundles can always be ranked

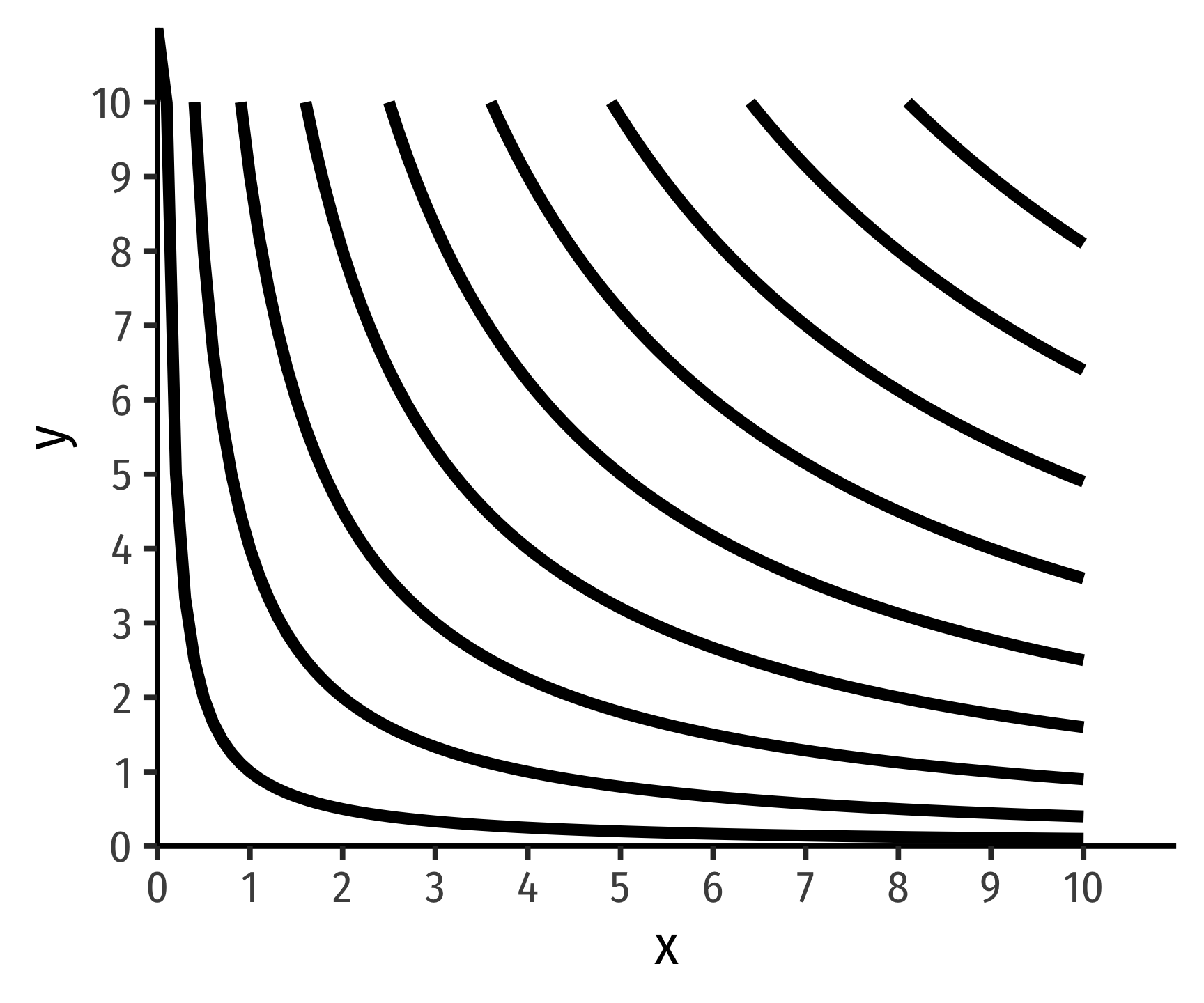

Every possible bundle (point on graph) is on an indifference curve.

Of course, this means that this entire graph is full of indifference curves - every single possible point is on some indifference curve (and this whole graph would just be a solid block of black). Naturally, it’s pointless to draw all the indifference curves, we just want to show a few to make our analysis meaningful. But the general idea comes from assumption 2 of preferences: any two bundles can be compared, as we can compare two points on this graph and make a judgment.

- Indifference curves are monotonic, which means practically that “more is preferred to less”

For any bundle

Here’s a challenge: what would indifference curves look like if one of the axes contained a bad, rather than a good? In this case, we would violate the assumption of monotonicity!

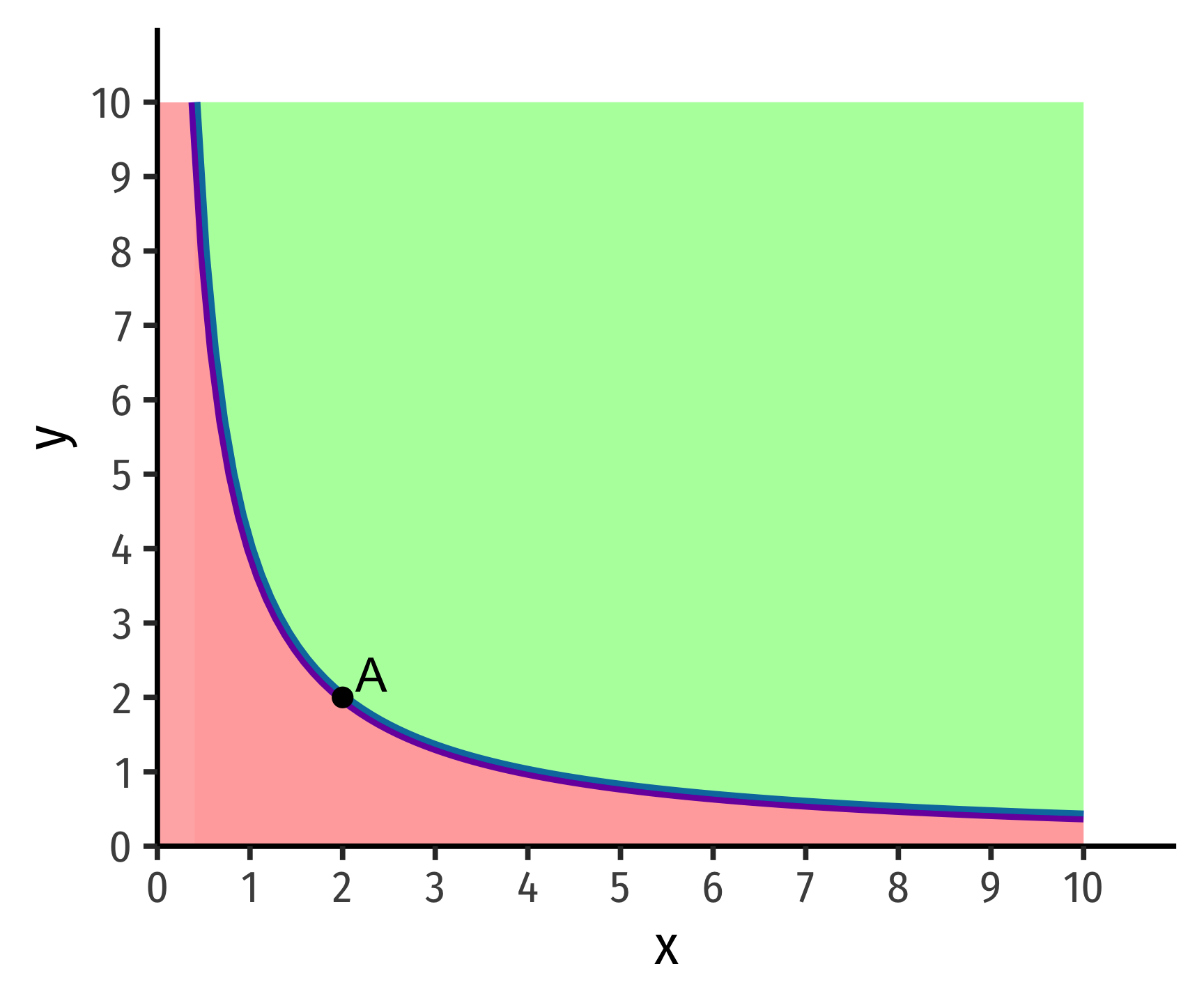

- Indifference curves are convex, which means in practice that “averages are preferred to extremes”

From experience, people generally prefer variety in their consumption. Rather than having one bundle that is “extreme” (a lot of one good and little or none of another), they tend to prefer a bundle with a better “mix” or “balance” of some of both goods.

Take our example from class, hunting for apartments. Apartment

Mathematically, this feature is because indifference curves are normally convex. A function is convex when a line connecting any two points on the function lies above the function itself. Check the math review guide for more information.

Here’s a challenge: what would non-convex (e.g. concave) curves look like, and what preferences would cause that situation?

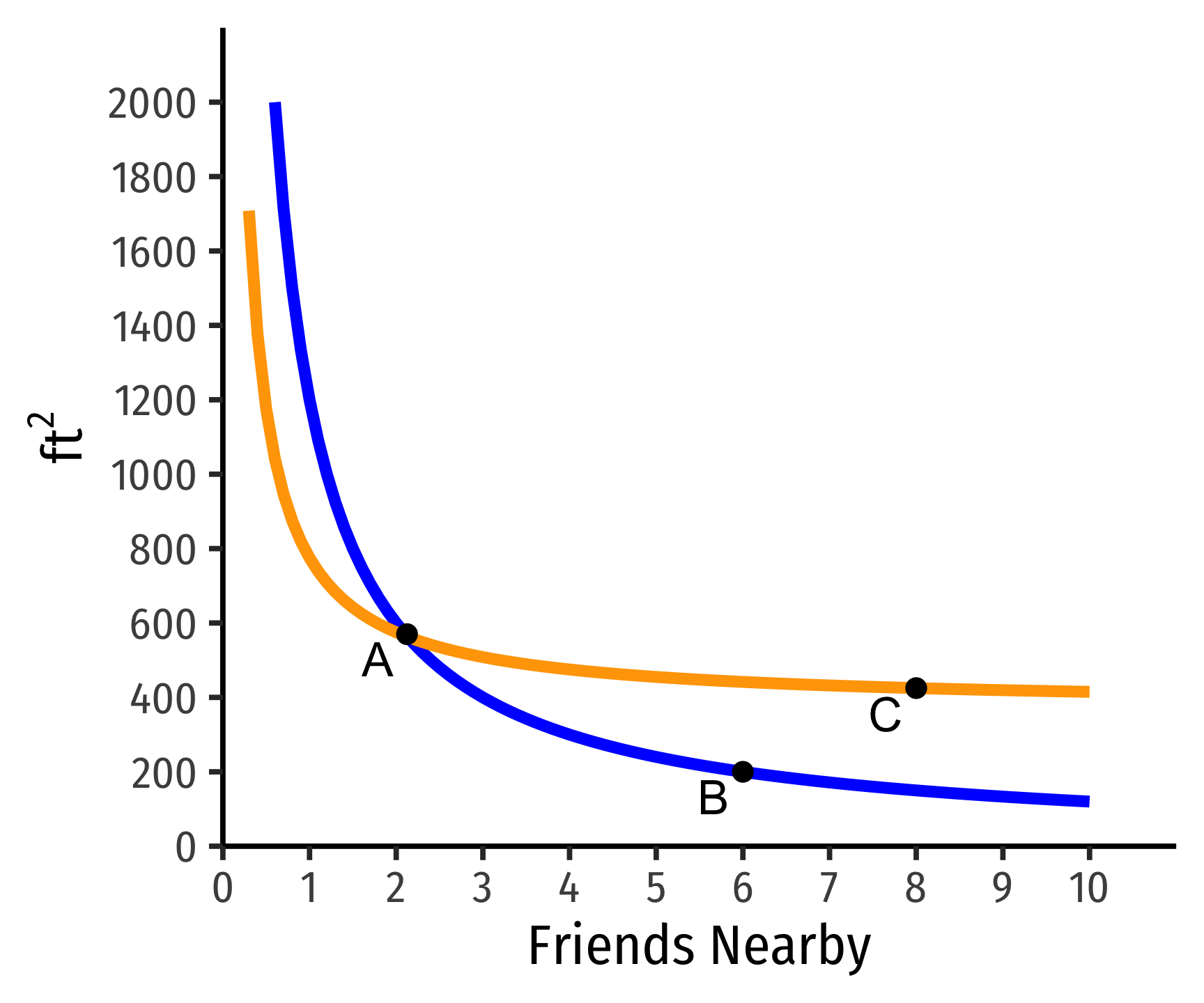

- Indifference curves can never cross because we have assumed that preferences are transitive.

Suppose two curves crossed, as the ones below:

- On the blue indifference curve,

- On the orange indifference curve

- But clearly

- Preferences are not transitive!

Steepness & Indifference Curves for Neutrals

The Steepness of indifference curves tells us how consumers trade off between goods.

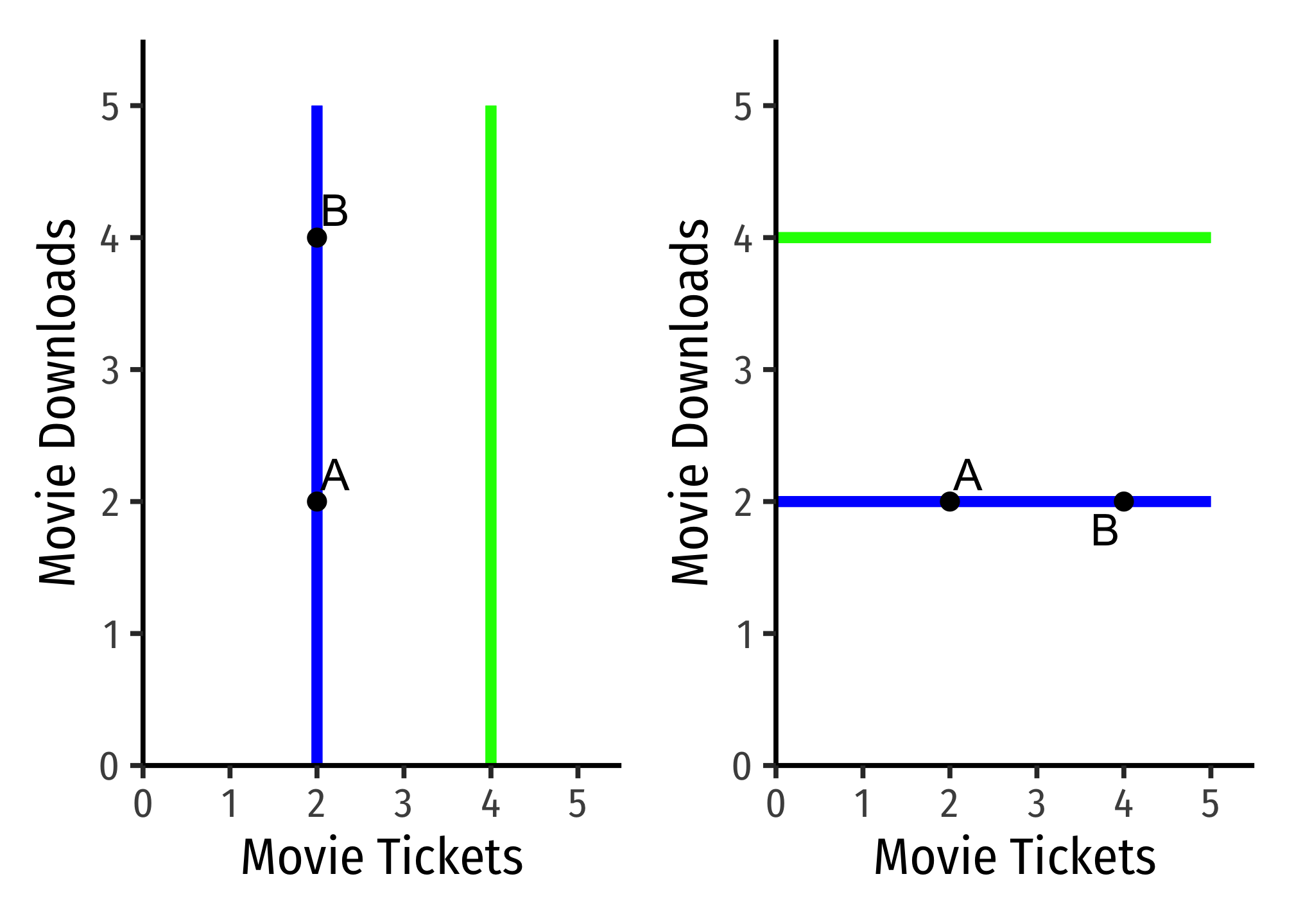

Perfectly vertical curves (left)

Perfectly horizontal curves (right)

We can look at less extreme cases:

On the left graph, the flatter curve implies the person is willing to give up only a few Downloads to obtain more Tickets (and vice versa).

On the right graph, the steeper curve implies the person is willing to give up a lot Downloads to obtain more Tickets (and vice versa).

Derivation of MRS Equation (as ratio of marginal utilities)

Consider a movement along an indifference curve, how would this change affect utility? There will be a change in

Notice rise over run,

Utility Functions and PMTs

Two utility functions

The following utility functions express the same preferences:

A positive monotonic transformation (PMT) transforms quantities such that the rank order of the quantities is preserved.

- Examples:

Any PMT of a utility function contains the same preferences!

Graphing Indifference Curves

I will not ask you to formally graph indifference curves (just roughly sketch them where appropriate). If you wanted to graph them, and express them in a graphable (slope-intercept form) equation, simply solve for the good on the vertical axis.

Example: Suppose we have a typical1 indifference curve for apples

Each indifference curve (or contour) is one level of utility (all points on the curve give a specific level of utility). So, set that level of utility equal to some constant,

Then, if we are putting

This is the general equation for all indifference curves of this utility function: each utility level (value of

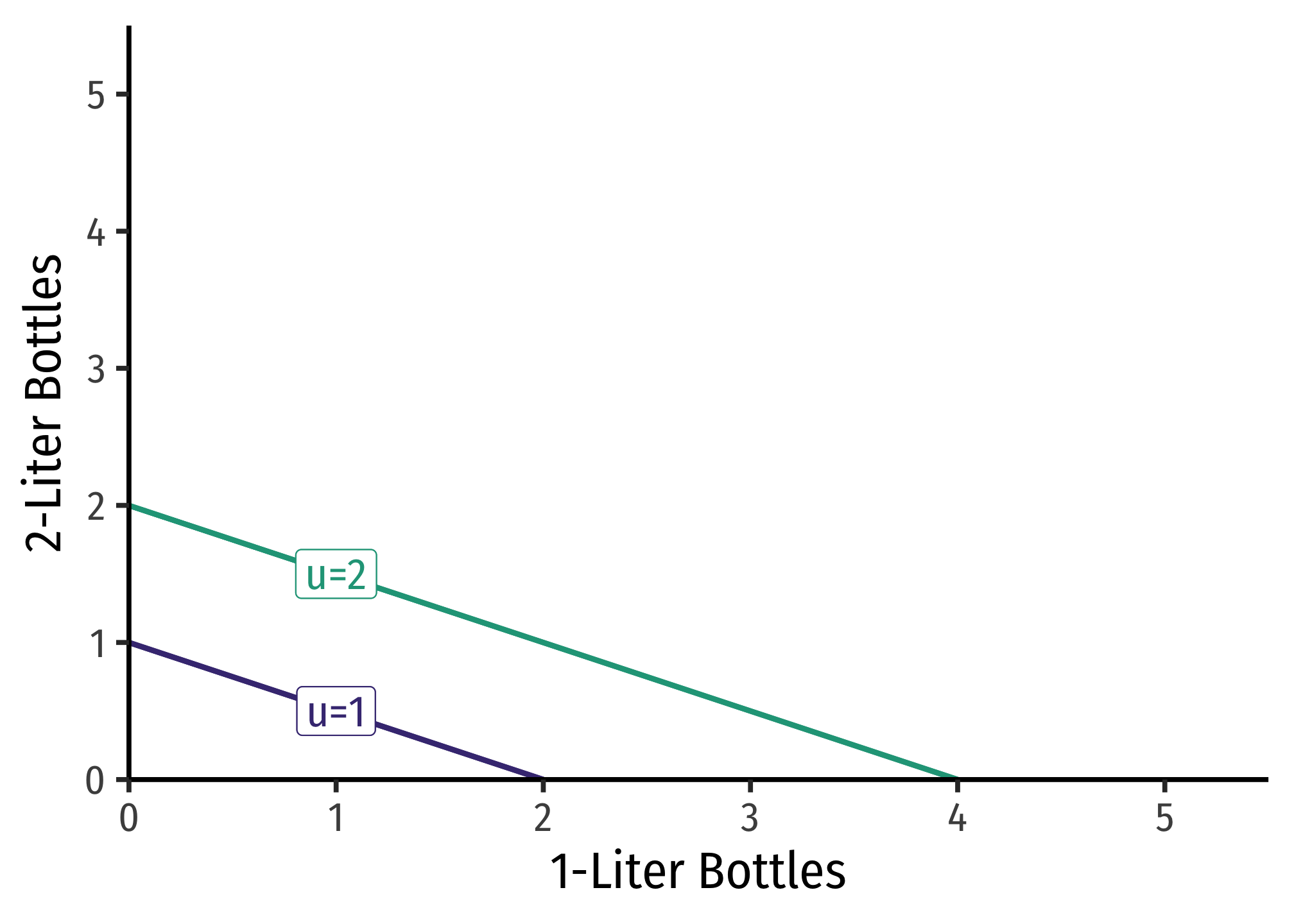

Utility Functions for Perfect Substitutes

Perfect substitutes produce straight lines for indifference curves. A straight line has a constant slope, which is interpretted as the MRS being constant - you should always be willing to substitute between the two goods at the same rate. The utility function looks like:

Where each

Notice, having some of one good and none of the other still provides positive utility (unlike utility functions where the quantities of goods are multiplied!). This is precisely because of the substitutability between the goods!

Example

Consider 1-Liter bottles of Coke

The relative weights here are 1 for 1-Liter bottles and 2 for 2-Liter bottles, because 2-Liter bottles are “worth” twice as much for you (it takes two 1-Liter bottles to match a 2-Liter bottle!).

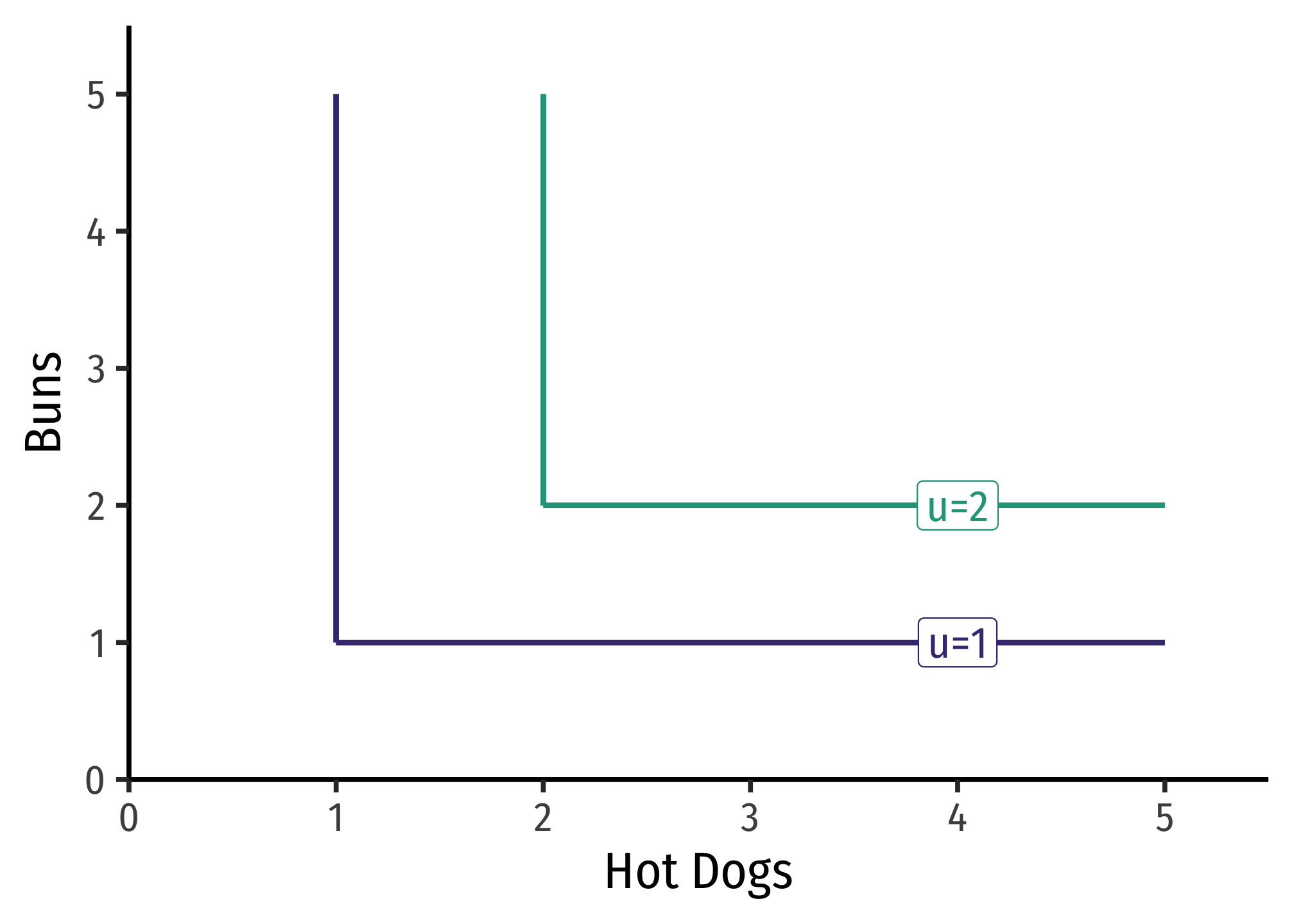

Utility Functions for Perfect Complements

Perfect complements produce right angles for indifference curves. This is technically not a mathematical function, since each

Where each

The marginal rate of substitution alternates between

Example

Consider consuming hot dogs

Having 2 hot dogs and 3 buns only yields a utility of 2. Having 3 hot dogs and 2 buns also only yields a utility of 2.

Cobb-Douglas Functions

Cobb-Douglas functions (both for utility and production) are one of the most common functional forms in economics. Despite their somewhat frightening presence on the surface, they have very neat mathematical properties, and have been empirically useful as well. A Cobb-Douglas function (for utility) looks like:

MRS and Positive Monotonic Transformations

The marginal rate of substitution, using the above equation is:

Using logarithms, we can take a positive monotonic transformation of the original utility function

The MRS using the logarithmic form is:

Which of course, is the same, because we know any positive monotonic transformation of a utility function preserves the same preferences!

EXAMPLE

Find the marginal rate of substitution for the utility function:

First, recognize that square roots are equivalent to saying

Note we could find this equivalently again by taking logs of the original utility function.

Which again, gives us the same marginal rate of substitution.

Footnotes

Cobb-Douglas!↩︎